Against Nietzsche

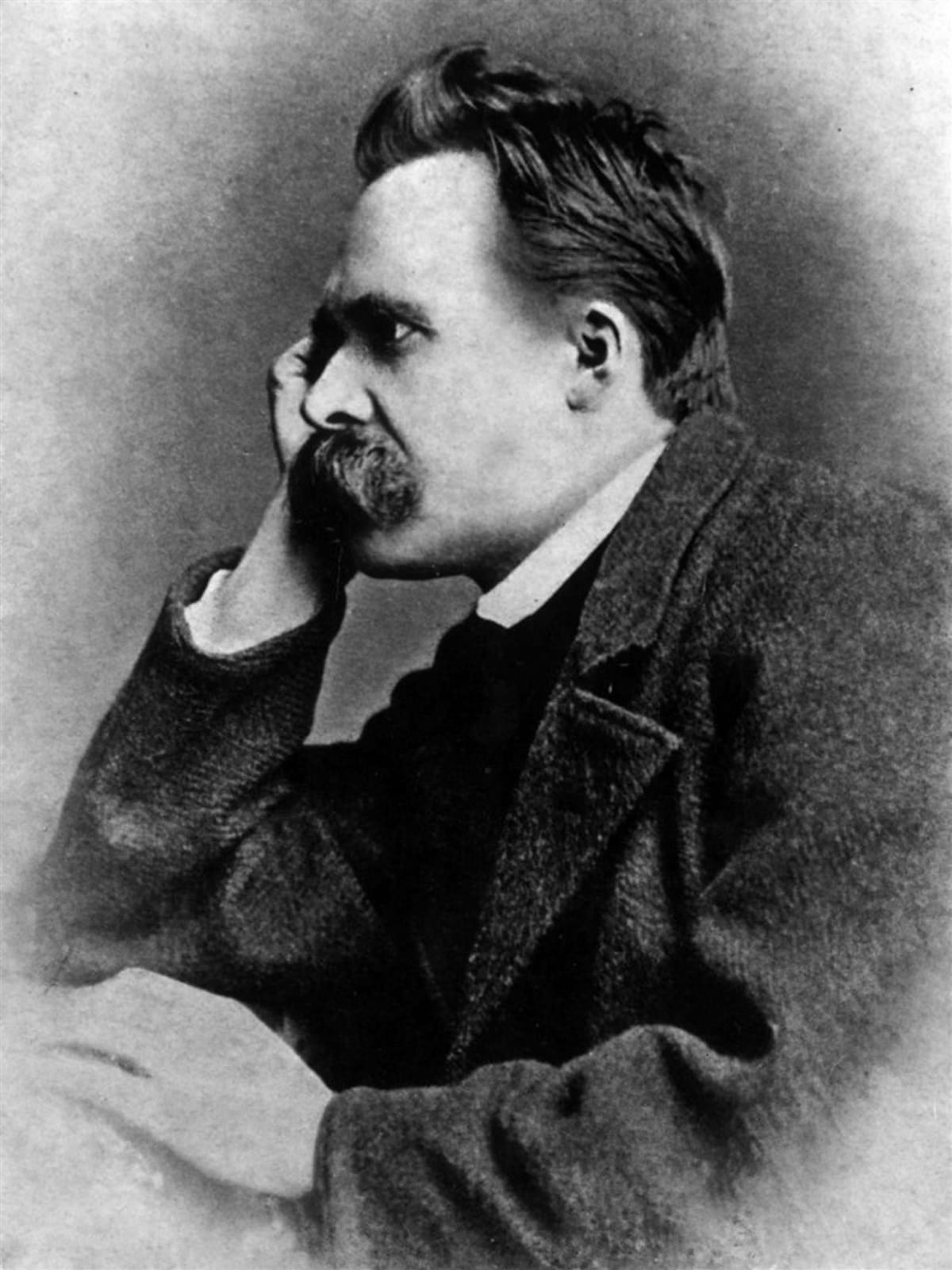

Since I have posted in favor of Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy not once, not twice, but three times, I think it is only right that I explore the more objectionable sides of Nietzsche, the parts of his philosophy I cannot accept.

I will say at the outset that all my feelings of hate reading Nietzsche are overcome by a deeper love. He wrote with freedom. Maybe no other philosopher wrote with as much freedom as he did—freedom of language as well as freedom of thought. He didn’t just indicate or imply what he meant, he said it directly. He didn’t disguise his thought as orthodox, he took unpopular stances and boldly declared what he believed. Consequently, no critic of Christianity is more devastating than Nietzsche. He was a non-conformist through and through, and a clever one. Unlike Kant, Hegel, Heidegger, Derrida, and countless others, Nietzsche didn’t cloak his ideas with jargon or force his readers to become safe-crackers; he bore his ideas out fully and clearly. Even when his ideas are elitist, his writing is democratic—unlike Derrida, whose ideas are democratic but whose writing is elitist. Nietzsche wrote with clarity, passion, and cunning, and I can’t help but find his writings—especially Thus Spoke Zarathustra—inspiring and challenging.

Having said that, I also think Nietzsche wrote some of the worst philosophy I’ve ever read. While Beyond Good and Evil is undoubtedly the work of free spirit, it also includes some incredibly alarming and harmful ideas. Let’s take a look.

Nietzsche’s concern in Beyond Good and Evil is to deconstruct morality. He maintains, there is no such thing as the Good in itself. The idea of the Good was invented by Plato, and Nietzsche calls it “the worst, the most tiresome, and the most dangerous of errors,” “the very inversion of truth, and the denial of the perspective … of life.”[1] Life is messy. It is in flux. It produces contrarieties and gradations of things varying in value. Even untruth is a condition of life, Nietzsche says, for “man” could not live without comparing reality to “logical fictions” and imagined worlds. He regards “even the emotions of hatred, envy, covetousness, and imperiousness as life-conditioning emotions, as factors which must be present … in the general economy of life.”[2] There is no good or evil, only varying instincts and compulsions which are brought about spontaneously by the life-process.

The life process, according to Nietzsche, is defined by Will to Power.[3] Consistent with this will to power, morality was a “slave-insurrection,” invented by the Jews to assert power over the powerful. The Hebrew prophets deemed those in power evil, and the sufferers good, and thereby inverted the values of those in power.[4] This transvaluation of values eventually led to the establishment of the church, which Nietzsche says exists to provide “comfort to the sufferers, courage to the oppressed and despairing, a staff and support to the helpless.” In so doing, Nietzsche believes the church has weakened humanity, coddling its weakest impulses. The church’s function has been “to shatter the strong, to spoil great hopes, to cast suspicion on the delight in beauty, to break down everything autonomous, manly, conquering, and imperious—all instincts which are natural to the highest and most successful type of ‘man’.” The Church has thus led “to the deterioration of the European race.”[5] (More on race in a minute.)

Nietzsche sees the movement toward equality as the inheritance of Christianity.[6] He devalues those whom he calls “the levelers,” who preach “Equality of Rights” and “Sympathy with all Sufferers.”[7] He says suffering is essential to the growth of humanity, and intolerance of suffering is a sign of deterioration and weakness. He objects to the “feminine” “hatred of suffering generally,” as well as “the unmanliness of that which is called ‘sympathy.’”[8] “We opposite ones,” he says, “believe that severity, violence, slavery, … that everything wicked, terrible, tyrannical, predatory, and serpentine in man, serves as well for the elevation of the human species as its opposite.”[9] This is Nietzsche’s transvaluation, a contradiction of Judeo-Christian-democratic morality.

Nietzsche’s philosophy is fundamentally elitist. “It is the business of the very few to be independent,” he wrote, “it is a privilege of the strong.”[10] And further: “how could there be a ‘common good’! The expression contradicts itself; that which can be common is always of small value.”[11] Equality, in Nietzsche’s judgment, would be “the destruction of the exceptional man.”[12] The creation of exceptional men is essentially the purpose of history for Nietzsche. His thinking is consistent with the Great Man theory.

As is typical of Great Man theories, Nietzsche’s philosophy is sexist. He objected to feminism, saying,

“The weaker sex has in no previous age been treated with so much respect by men as at present. … That woman should venture forward when the fear-inspiring quality in man—or, more definitely, the man in man—is no longer either desired or fully developed, is reasonable enough and also intelligible enough; what is more difficult to understand is that precisely thereby—woman deteriorates.”[13]

What makes men men is their “fear-inspiring quality.” As the church weakens this quality through morality, as sympathy with sufferers becomes the norm, people become more democratic, men become more timid, and women assert more power. Whereas for Nietzsche, greatness requires bold, daring, conquering men of steel, who inspire women to be subordinate through the spectacle of their sheer strength.

Nietzsche’s great men are the product of a life-process which he says concern “physiological valuations and racial conditions.”[14] “People have always to be born to a high station,” he says, “or, more definitively, they have to be bred for it … the ancestors, the ‘blood,’ decide here also.”[15] So Nietzsche’s philosophy is racist. He explicitly says the deterioration of the European race is due in part to “a senseless, precipitate attempt at a radical blending of classes, and consequently of races.”[16] He calls this class- and race-mingling a “mad semi-barbarity.”[17] And as much as he spoke against anti-semites in his own time, he still saw morality as a Judaizing of Europe, and objected to it decisively.

My least favorite Nietzsche quote, however, is the following one:

“Every elevation of the type ‘man,’ has hitherto been the work of an aristocratic society—and so will it always be—a society believing in a long scale of gradations of rank and differences of worth among human beings, and requiring slavery in some form or other.”[18]

And so Nietzsche solidified his support of a caste system, for “always.” Some are rich, others are poor. Some are powerful, others are powerless. Some command, others obey. Some are masters, others are slaves. So it has always been, “and so will it always be.” It is good and right, it is life itself, for there to be inequality, oppression, and slavery. Suffering persists for the sake of the few, for the sake of great, exceptional men, who create values, who decide for themselves what is good and bad. He praised Napoleon, calling him “a blessing,” as an “absolute ruler” who commanded rather than obeyed.[19]

Nietzsche also expressed a desire that Europe would “acquire one will, by means of a new caste to rule over the Continent, a persistent, dreadful will of its own, that can set its aims thousands of years ahead,” bringing “its democratic many-willed-ness … to a close.”[20] Here is the philosophical foundation for fascism, a system of government based on the will of one man, to whose will an entire continent would conform. Is Hitler not one of Nietzsche’s great men? Is Trump not one of Nietzsche’s great men? These history-steering tyrants who impose their will absolutely and seek greatness through conquest?

As unjust as Nietzsche’s sister’s cooption of his work for the cause of Nazism was, it’s not the least bit surprising that Hitler was enticed by Nietzsche’s writings. “You want, if possible … to do away with suffering,” Nietzsche wrote, but “we,”—that is, real philosophers—“would rather have it increased and made worse than it has ever been!”[21] Well, he got his wish. With Hitler, suffering was increased and, arguably, made worse than it had ever been. And Nietzsche’s name was invoked in the process. His popularity among Hitler and the Nazis is well-documented.

So why not stop reading Nietzsche altogether? I certainly do not blame anyone for refusing to read Nietzsche. I read him because, as I said, he wrote with freedom and clarity, and I find him exceedingly helpful when it comes to learning to love life and love myself. He was also just wicked smart, and had a profound ability to cut through to the center of an issue and challenge its fundamental premise. Something that can be said in his favor is that he was not a dogmatic or systematic philosopher. He shunned systems and resisted the impulse to sequentialize thought, writing in aphorisms and short essays rather than long-winded treatises. He regarded himself as a philosopher of “perhaps,” and so he held his ideas with a looser grip than most. That makes it easier to take his writing with a grain of salt.

But the worst of his philosophy does stop me from becoming a Nietzschean. You’ll notice all my Nietzsche reading has not shaken my commitment to socialism the least bit. Nor have I relinquished my hold on the concept of morality. I’m all for slave insurrections, and I look forward to the day when caste societies and aristocracies are overcome once and for all.

Along the way, I think it’s healthy to keep a good critic at hand, someone who dares to think oppositely, who dares to challenge even our brightest and most noble ideas. Nietzsche was a hell of a critic, but he was also a kind of chauvinistic troll.

Jack Holloway

Footnotes:

[1] Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, trans. Helen Zimmern (Buffalo: Prometheus, 1989), 2.

[2] Nietzsche, 33.

[3] Nietzsche, 20.

[4] Nietzsche, 117.

[5] Nietzsche, 83.

[6] Nietzsche, 127.

[7] Nietzsche, 58-59.

[8] Nietzsche, 259.

[9] Nietzsche, 59.

[10] Nietzsche, 43.

[11] Nietzsche, 58.

[12] Nietzsche, 139.

[13] Nietzsche, 187-188.

[14] Nietzsche, 29.

[15] Nietzsche, 156-157.

[16] Nietzsche, 144.

[17] Nietzsche, 167.

[18] Nietzsche, 223.

[19] Nietzsche, 121.

[20] Nietzsche, 146.

[21] Nietzsche, 170.